“Ultimately, their expedition had one inevitable end, one final grave at the center of the spiral, and they all knew it…”

Mili’s prologue—————————————————————————————————->

For the last several months, I’ve been deep in work on a new mini-comic. Set against a back drop of rising Christian-nationalist sentiment, the work has me doodling devils, etching angels and rooting up the spiritual baggage of my early childhood. On a crusade fueled by righteous indignation, deep in the swirling thoughts of my drafting solitude, I bumped up against a wall crafted from the natural limitations of my own devout faithless-ness. Stuck. I began to crave conversations with other cartoonists who might be tackling similar themes. What were they thinking? How were they feeling? What sorts of texts and perspectives were pushing them forward?

As luck would have it, in April of this year, I encountered one J. Marshall Smith while moderating a panel on comic burnout. The panel featured both Smith and his publisher, Zach Clemente of Bulgilhan Press, who let it slip that Smith was working on a new sci-fi book called Testament.

“It whoops ass!”, both assured me.

Motivated by such a lofty guarantee, I began familiarizing myself with Smith’s existing works. Good Girl Laika, a mini comic about a dog stuck alone in space and Solace County, an anthology collection of many works. They were existential, they were emotional, but most of all, they were kind.

When a PDF of Testament landed in my email some many months later, I read it immediately. It was existential, it was emotional, it was kind, but most of all, it whooped ass.

Conveniently, I was surprised to find that the book tackled grand themes of faith and religiosity with deep empathy, contrary to my own fire and brimstone approach.

I asked J. Marshall Smith if he might want to do a written interview, primarily because I had so many questions to ask him, and also because I thought his answers and perspectives might help others as well. What follows is a deeper reading of J. Marshall Smith’s new work, Testament. Please enjoy and thank you so much to J. Marshall Smith for joining me!

Interview Start —————!contains spoilers—————————->

Follow J. Marshall Smith:

Website // Instagram // Patreon // Buy Testament

>>Mili:

Your new book, Testament, is a beautiful sci-fi space adventure that follows a colony of nuns who are artists, poets and scientists as they settle a new planet to explore life on it…

Below the surface, the book offers a devastating meditation on Christian themes like faith, creation and humanity. Many artists are choosing to grapple with their religious roots in this moment, but Testament feels unique in the kindness it approaches the topic with.

What led you to write Testament and why did it feel particularly important to write now?

>>Jonathan:

It is funny, I never thought of Testament as an especially timely story…

For me, it is a very personal story and informed by my own history and interests and I was honestly a bit concerned no one else would connect with it at all. It is still early days, but I’m happy to say it has found some readers that have resonated with it.

Part of why I wrote this book is because I looked around and I didn’t see anyone else writing about Christianity, or any other religions or belief structures, with any kind of experience or skill.

You either had people who have no experience with faith creating caricatures, or you have believers making work for an insular “Christian Market” —a concept I have always found abhorent— and nobody seemed to be speaking to my experience. There are a few, and more in comics now than there were, but ultimately no one can tell your story but yourself.

It would take a lot of time and skill that I don’t have to say anything fair and true about something as big, complex, and diverse as Christianity. Certainly there are and have always been people that wield the church to commit horrible sins in the name of power and empire, but also many of the strongest opponents of those injustices have also been Christians acting out their faith. I think we are seeing a generation of people who were raised in the church who are questioning their spiritual and cultural inheritance. Some of those people make comics, and some of those people are making comics about that experience. This is due in large part to how many churches, or at least our cultural imagination of what Christianity is, has largely abandoned the teachings and character of Christ in favor of Mammon and christofascist empire. In a very real sense, I think many Christians today and historically worship Christianity, and the Church itself becomes an idol instead of a way to know God. That’s like receiving love letters and having an affair with the postal worker who delivers them.

Ultimately, I discovered two big animating desires in the story as I wrote it. One,

>>“I wanted to imagine a future sect of Christianity that I liked more than the ones I see today.”

Two, a lot of robot science fiction asks us to question how we define humanity, and I’ve never really seen those questions applied in an ecclesiastical setting. I think the question of faith and how it is gained is very interesting. If you can program a being with thousands of years of theological and philosophical knowledge, ritual and liturgical practice, where does faith start? If a machine can think, can it pray? If you create an immortal being to want to care for you and then die and leave it alone forever, are you condemning it to some kind of Hell?

I’m glad that you think of my approach as kind. I’ve had other readers describe it as brutal and harrowing. I think a lot of people, if they are writing about religion, are preoccupied with the question of whether or not it is true. They are trying to convert the reader to belief or disbelief and I am not interested in that. I think of Testament as a portrait of faith, not a case for it.

>>Mili:

I would love to talk about the nuns as you’ve grounded their stories and characterizations in so much honesty. My mother was a care worker for aging nuns for many years and suffered a tremendous amount of grief as she nursed each sister through to their eventual death. She always spoke of their stories, their immense accomplishments and of their enthusiasm for learning. Indeed, as Orders face extinction, there are potentially many Sister Judith’s in the world.

What made you interested in writing about nuns and what was your inspiration for Sister Judith?

>>Jonathan:

First of all, your mom sounds really cool! That is really admirable work. I wish I had been able to talk to her when I was writing the book!

I chose to write about the Order of the Abundant Grace of the Cosmic Christ for a few reasons. The first is practical. I only had a few pages to talk about the community Testament was serving and the fastest shorthand was to make them a monastic sect with visual cues. Although the Sisters’ “habit” is not a strict rule, and I imagine them as fairly anarchic —in early versions there were some topless sisters walking around— having visual work do some of the worldbuilding helps tell a story quickly.

The second reason is that I don’t have firsthand experience with any kind of monastic orders but I think they are really interesting. Maybe having no experience is a reason NOT to write about something, but my creative process has always been more animated by questions than answers. I wanted to come up with a new sect because I hate the idea that the church would not change and no new variations would bloom, but also it frees me from misrepresenting a real world monastic order, which I think would be disrespectful. I don’t think of them as Catholic, or any specific Protestant variation. Most of the future Testament takes place in is secular, and I don’t imagine most people would even be aware they exist.

The third reason is also practical. I imagine about 80% of the expedition to this new planet is made of members of Sisters and Nonbinary members of the Order. If you have an amazing planet at the far frontier of where human space travel can reach and you know you won’t be returning to Earth or any of its colonies, having a base of volunteers who don’t have children, are highly educated and curious, and have already chosen a life apart from others just makes sense.

The Order’s name isn’t just a bunch of fun sci-fi words. It has specific theological implications. Abundant Grace is unlimited, unearned, and unlooked for. The Cosmic Christ is a christological idea that decenters humanity from the redemptive work of Christ and emphasizes God’s love for all of creation. It is a part of the theology of many religious scientists. Those two ideas together are the theological and moral foundation of their sect. They think humanity's purpose is to be a part of the world, to see it, and to marvel. They have dedicated their lives and deaths to that purpose.

>>Mili:

Your story follows Testament, a fully autonomous and devoutly Christian robot built to care for the members of the colony until their deaths.

Why did you choose carework to explore the line between humanity and simulacrum? Has your perspective on where the line is shifted at all from when you started the book to when you finished it?

>>Jonathan:

Not to be difficult, but I’m not sure if Testament is either autonomous or Christian. I guess the question of how we define those things are at the core of the book. I wrote it and I’m not sure I have answers myself.

I wouldn’t say Testament is fully autonomous because they never break with the directives described in the early part of the book. They were made to protect and maintain United Colonial Fleet Authority property and personnel. They would probably think of themselves as property more than personnel. This programming dooms them to live forever without the people those same directives compel them to care for. Then again, being subject to impossible desires is a very human experience. In the end Judith demonstrates a level of ultimate self-destructive autonomy that Testament is, for better or worse, incapable of.

Likewise, I’m not sure Testament is a Christian. Certainly they are christianized, but does being steeped in the lore and practice of a religion make you an adherent? For a religion ideally defined by divine forgiveness of mortal transgressions, how important is adherence? Where is the line? They have a perfect memory of every religious treatise, ritual, and prayer ever published but does that make them a Christian? I don’t think so. Most of how people think about Christianity is in relation to sin, sacrifice, and forgiveness. Did Jesus die for Testament’s sins? Is Testament even capable of sin? For many people, their chief concern with Christianity is an afterlife and avoiding damnation. Even if Testament has a soul, they will probably never die excluding some kind of cataclysm, so the afterlife is not really a concern. They still care a great deal about if and how they can relate to God. Does that make them a Christian?

I’m sure it is annoying for me to have more questions than answers, but I think any catechism should start with an introduction that says “these are our best guesses but we are almost certainly wrong about some of it”. I’m not saying there are no answers, but I think any answer that puts God and oneself in a neat little box of knowledge that can be possessed, instead of a vulnerable and relational kind of knowing shouldn’t be trusted.

I know that the Order of the Abundant Grace of The Cosmic Christ would have a lot of fun debating it. They are Christians, certainly, but because of their focus on an abiding, abundant, redemptive love for all things I don’t think it would matter to most of them either way. I don’t imagine Testament was ever baptised, if that matters.

>>Mili:

You make it very clear at the end of your book that Testament the robot is not meant to be a commentary on the artificial intelligence of today and rather, is a story about humanity like other stories about robots, golems and homunculi.

Why was it important for you to make this clarification? What are some examples of these stories and did any inspire your characterization of Testament?

>>Jonathan:

As a writer, I want to trust my reader and often choose to give them as much interpretive room as possible. I try to give them as much opportunity to invest their own thoughts and feelings into a story as I can get away with. However, I think cultural literacy and critical thinking are in a perilous position these days, especially with people who use LLMs. I’ve already had some readers drawing lines between Testament and what they call “AI” now, and I find that alarming. I think LLMs are a desecration of human art and labor, of the mind, heart, and skill of the person who uses them, the person who must see their slop, and of the Earth. They are evil, stupid, and embarrassing.

As far as other stories in that heritage, there’s all kinds of stuff. The Pygmalion myth, the golem stories, Frankenstein, etc. I think specific robot ancestors for Testament are the Iron Giant, Data from Star Trek, Tima from the Rintaro/Otomo/Tezuka version of Metropolis. I haven’t seen Big Hero 6 but I think there is a caregiver robot in it with an inflatable body and that idea must have snuck into the idea for Testaments malleable outer layer. I mean, who wants to hug C-3PO?

>>Mili:

Testament maintains a semi-humanoid facade throughout the book, presumably for the comfort of the nuns, but there is a moment where Testament’s mask briefly slips.

Why was this moment so important to include?

>>Jonathan:

I like Testament. I love all my characters even though I make bad things happen to them, but within the world of the story, Testament is designed to be likable. Not only that, they are designed to be sensitive to the comfort of humans and adaptive to their needs. The technology is there for Testament to appear as human as they want, but they center themselves around what is best for humans. They know people don’t want them to look too human. It would make them uncomfortable and threaten their image of self and humanity.

I want the reader to care for Testament but I don’t want them to forget that they are ultimately inhuman. That scene is there to remind them of that, and revive a bit of disquiet. It isn’t the first instance of discomfort in the book for me. The first time we see Testament speaking they are leading a funeral and that is uncomfortable for me. I don’t want people’s worship to be automated. Even if we see Testament as equally called to religious practice, I find it disturbing to see the Sisters cede the leadership of this ritual and the eulogy to their helper. At the same time, I am sure the Sisters are numbed by the majority of their loved ones dying in the past handful of years as they have grown old. I am sure that it is easier to let the helpful robot take over.

I imagine that is a dynamic that happened without them realizing it. As the human community dwindles, Testament becomes more socially and emotionally proactive to compensate. People need each other, and I think a big part of Testament’s “mask” is trying to give people what they need. After Judith’s death, Testament finally abandons their face entirely, retreating from expression or abandoning a performance. It is up to the reader to decide if they are abandoning a mask or abandoning their face in grief.

This scene is also the time when we see what Testament does while Judith is asleep. They fill the time when humans are asleep by practicing humanity. At first they practice cartoonishly simple expressions of emotion. Eventually they put on more complex humanity, the sort of faces they do not allow themselves when perceived by humans. They put on the face of the beloved dead. When Testament has a moment of private they work through ways to give Judith the emotional care that she needs, but they also work through their own grief by putting on death in a way. I think this grief is real but also alien to our experiences as mortals.

A lot of Testament’s behavior is calculated and centered around care for their people.The thing that gets Judith to really see Testament is Testament’s expression of need. Their need for her; the need to not be alone. This is the thing that makes Judith rethink her pursuit of death. Of course, it is in Testament’s programming to preserve and maintain expedition personnel, and the best thing to save Judith is to make her understand that she is needed, to give her someone to love.

Testament’s most extreme expressions in the story are at Judith’s death. Personally, although Testament is artificial, and their desires are programmed in, I think of them as completely honest, completely earnest. It is at the point of her death, when Testament is voicing a desperate and hopeless prayer for help, that I think of they are closest to humanity.

>>Mili:

Beyond care work, Testament also functions as an enforcer of faith by constantly reciting from a database of thousands of religious texts. This limitation produces the main conflict between Testament and Sister Judith as she searches for meaning beyond religion in her grief.

Why did you choose to give Testament this limitation?

Could you give us a behind the scenes look into why you chose some of these included texts?

>>Jonathan:

Community and human connection is an essential religious practice, At least that's what I think. The Kingdom of God, theoretically, is revealed through care and community. By being hurt and healed and cared for. People are for each other, and Testament is for people. Community, and the dwindling of it, is essential to this story.

Community, especially religious community, can also be a burden and an obstacle. There are certainly members of this expedition who are not members to the Order, are not Christian, are of other religions, or have no active spiritual practice. Testament equally cares for these people as well. When serving the Muslim explorers on this expedition they talk to them about the Quran with equal proficiency and care.

This story specifically focuses on a portrait of Christian faith, despair, and suicidality. There are beautiful expressions of all these things found in the Bible and other Christian hertiage. Sometimes seeing one’s misery echoed in scripture is a comfort. Testament hopes that the Bible will be a comfort to Judith as she faces decades of life without her community, without her family. When Judith allows Testament to recite scripture to her, she does not expect to be affected by it but she is. She must flee the intimacy of that moment and walk into the dark desolation of the landscape outside their fire. However, the effect it has on her quickly dwindles as Testament continues to barrage her with it. Until now, Testament has helped humans be in community but this is different, and reciting scripture at her fails to reach her after a short time.

As far as the specific passages I chose, I focused on expressions of despair, doubt, and a feeling of abandonment by God. I think something that might surprise people is that there are a lot of options for that in the Bible and while some of them affirm a desire to trust God, many of them do not. Testament is not correcting Judith’s despair with these passages, but is hoping to remind her that God is with her in her grief. Ultimately this cannot work purpetually.

>>Mili:

What is your favorite moment in the book and why?

>>Jonathan:

That’s tough. It is a short book and I really only put stuff in there that I really love, trimming everything else away. For the sake of having an answer, here are three moments I especially love:

When we get our first real look at young Judith, and she runs out in the snow with a quilt wrapped around her. She has the hopeful and contented smile of someone who is loved and free. Since most of the book is focused on her unhappiness I really love this scene because I like to imagine the many happy and fulfilling years. That is the same quilt Philomena has on her lap decades later, patched and repaired and cared for. It is based on a quilt in my actual life that I have a lot of potent memories associated with.

There is a page where we see glimpses of Testament and Philomena in her final days. They bathe her, she reads to them, they both sit in quietude, Testament carries her like a small child. I really love Philomena and I like this scene a lot.

Those first two are happy scenes. My third choice is a sad one. After Judith’s death, Testament carries her body across the desert, abandoning the Rambler, their ambulatory truck. Testament has recently jumped off a cliff unscathed and they pass through this powerful storm, and it cannot hurt either of them now. I like this scene a lot because it was fun to draw but also I feel like it really highlights the almost godlike power and absolute powerlessness of Testament in that moment.

Art talk ——————————————————————————————————->

>>Mili:

What was your process for developing the overall visual look of this book and its characters? What inspirations did you draw from (and can we see some early process pictures?)

>>Jonathan:

I like working with a simple two color palette with one halftone variation. I use a lot of smudgy messy ink drawing and then scan it on a black and white threshold. I think the interaction between very human messy drawing and mechanical elements like halftones is interesting and beautiful. I guess that’s also the theme of the story too.

A few folks have pointed out that Sister Judith looks kind of like Ursula K Le Guin, and I can see it. Especially since this is “big ideas in space” style science fiction. I love her work, but that was unintentional. Her look was largely informed by older women in my own life. She is kind of masc in a tough old lady kind of way, but I also think gender and sexuality constructs in the future would naturally be different from our own. It was important to me that she was old but healthy and not so old that with the constant care of her robotic nurse she couldn’t live for another couple decades at least.

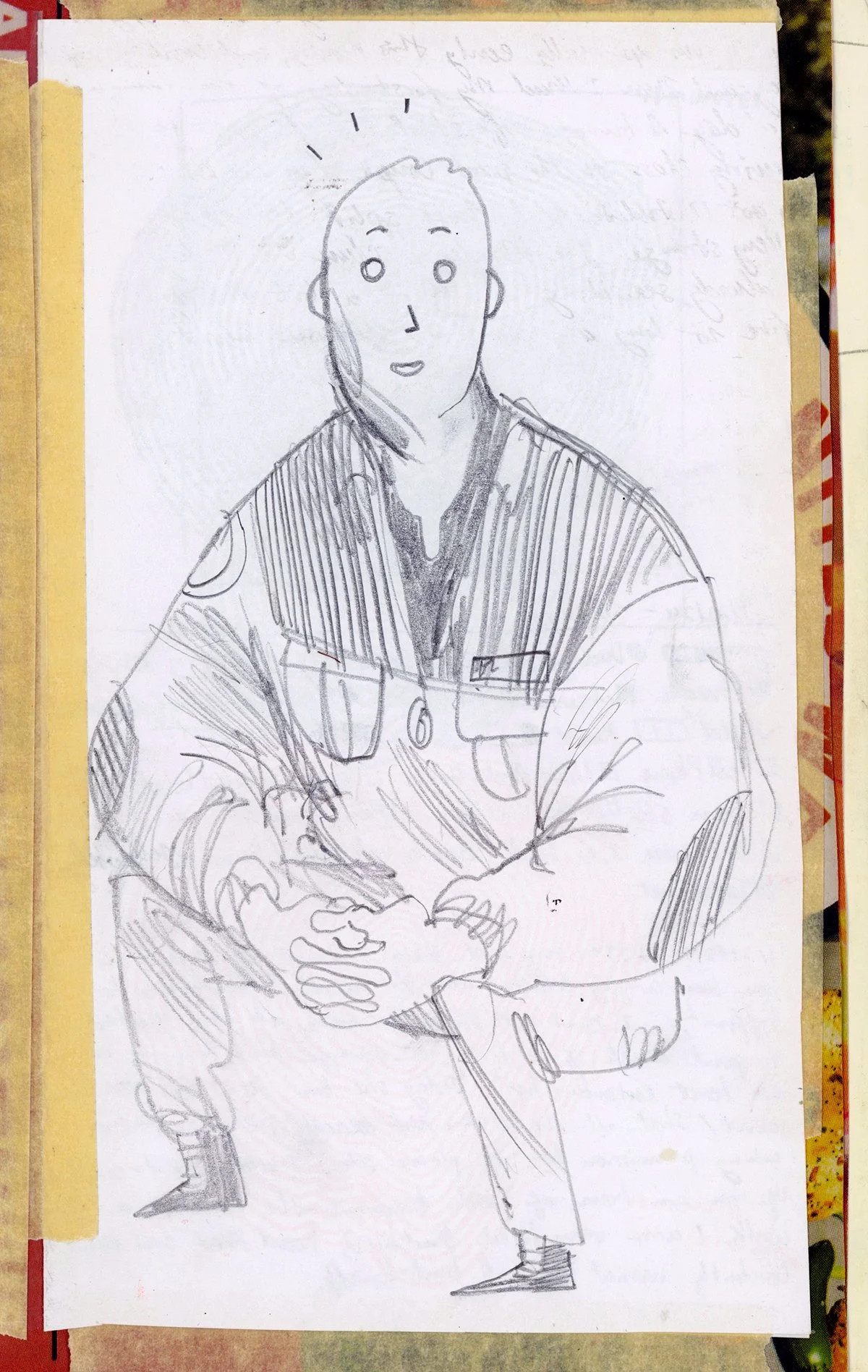

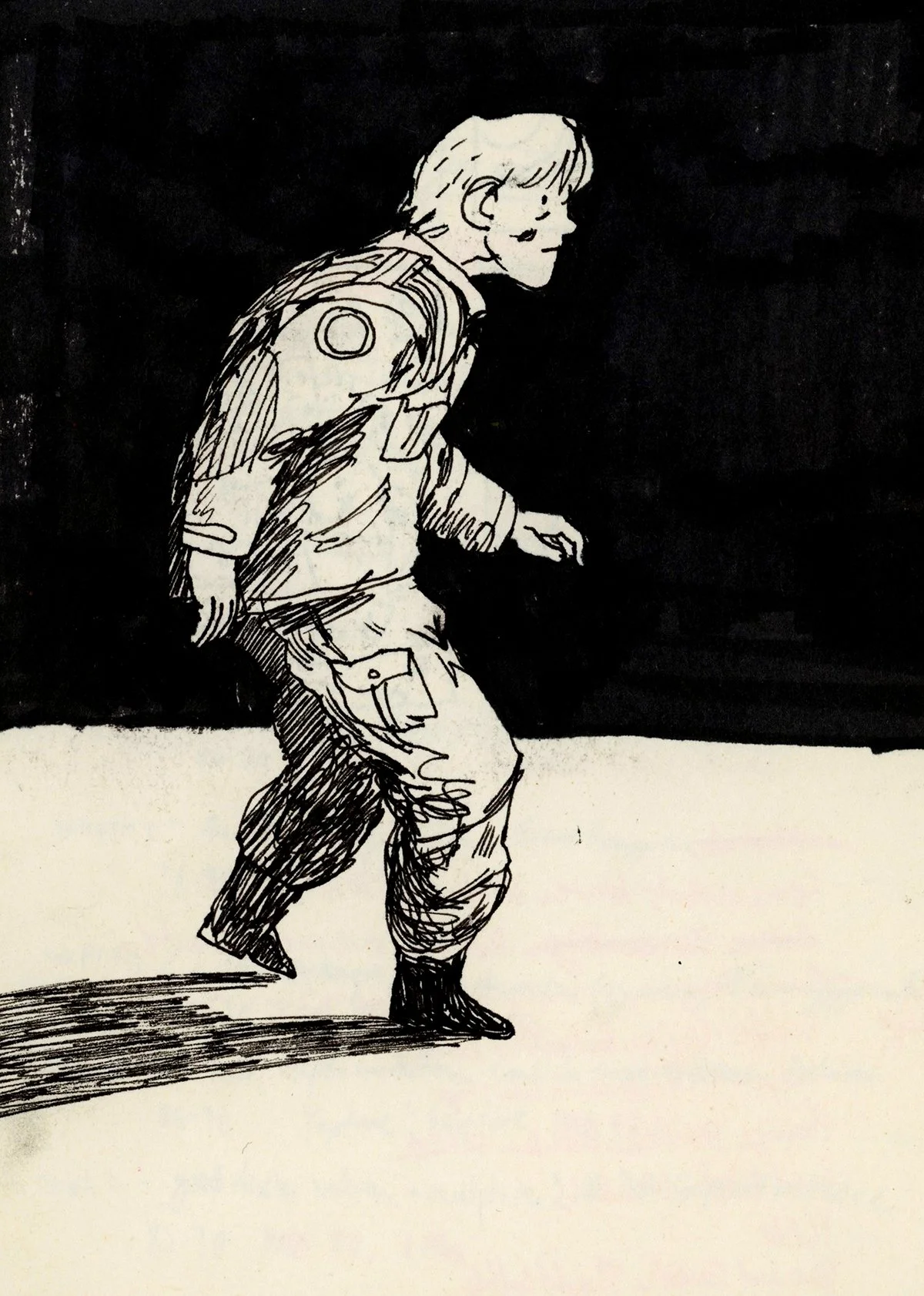

I touched on this a bit before but Testament is large and powerful looking but ultimately soft. Their design uses the most simple, inhuman, cartooning. They are simple, appealing, and expressive. They wear a Colonial Fleet jumpsuit all the time, but I imagine there were some Sisters who made them different clothing at some point as a gift.

Early designs for Testament were much more metallic and mechanical. A classic metal robot man who wore clothing here and there as a mirroring of humanity. Ultimately I moved away from that because I didn’t like drawing them and those designs did not speak to Testament’s role in the story or what their function is within the expedition.

Philomena’s design never really changed. She bloomed like that right away. I knew I wanted a Sister that wore her habit all the time while Judith doesn’t, and I don’t think of that is a symbol of faithfulness but knowing that she was older and disabled I liked the idea of the special effort she put into wearing her clothes and how Testament or Judith helped her. I love her because she is old and wrinkly and fat and beautiful. May we all be so lucky!

>>Mili:

The ever-growing circle of graves is particularly visually haunting. How did you decide on this pattern and is there any hidden symbolism here?

>>Jonathan:

Thank you! Initially I had the graves set up in a fairly predictable grid, although I had known I wanted them to use unhewn stones for their markers. About halfway through the book I realized that they know exactly how many graves they will need, how much space those graves will take, and that these people would likely use that opportunity for some art.

A lot of people have given their bodies to science, and some have used their bodies in interesting burials or sacred art. It was inspired by Catholic reliquaries, but also standing stones from different pagan traditions, and meditation labyrinths. Ultimately, their expedition had one inevitable end, one final grave at the center of the spiral, and they all knew it. The issue, perhaps the cruelty, is that it isn’t over. Testament remains.

I chose the name Testament for two reasons. First, is the obvious biblical connotation. The second is the association with a last will and testament after someone’s death. The spiral of graves is a memorial, a testament, to the memory of these human explorers, but so is the android. They are the final message and memorial of these people, blessed and cursed to remember them forever.

>>Mili:

What drawings or page(s) from the book are you most proud of and why?

>>Jonathan:

I liked drawing all the weird little alien critters. I wanted most of the natural life on this planet to feel primeval, pre-dinosaur, in its evolution. Lots of bugs and crabs and creeping things. There is a kind of fish creature at the end that links up in a line that I think the Sisters called a “winged chainfish”.

I like the drawings of clouds throughout the book. The storm that Testament carries Judith through to take her home. The silence of heaven at the end.

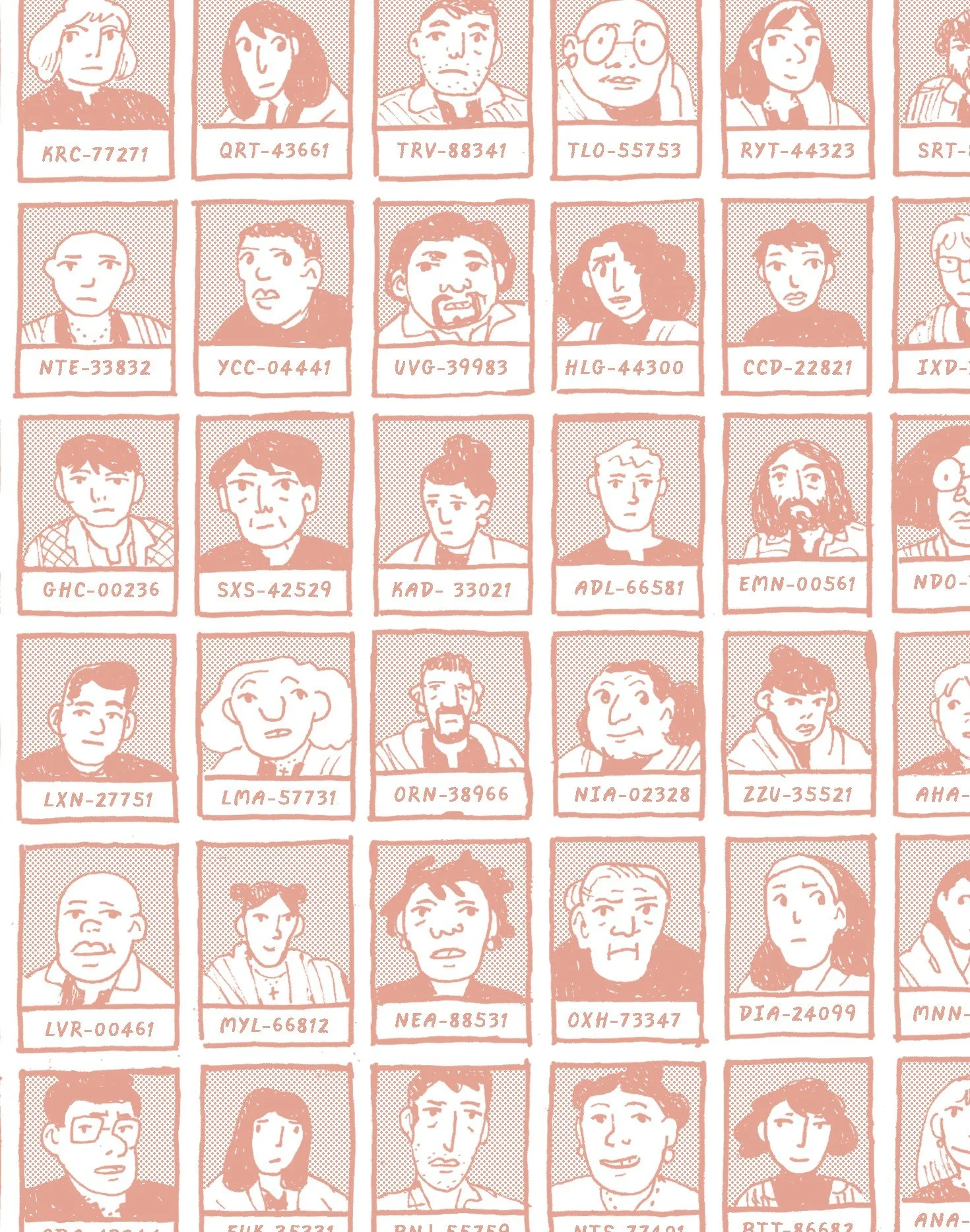

I like a lot of drawings in the book although they are all blessed with imperfections. One of the drawings I most enjoyed was the spread of some of the human explorers’s ID photos early in the book. We just have their pictures and ID numbers, how they are recorded by the powers that hurled them across the cosmos to be here. It is at once dehumanizing but they are also an inventory that Testament tirelessly watched over for years and years as they hurtled through the quiet of space, counting the minutes until they wake and they can meet. I loved drawing them all and thinking about all their adventures, loves, and fears even though I knew I wasn’t going to put any of that in the book. I killed them all at the beginning of the book but I loved thinking about them.

>>Mili:

When I saw you at CxC, you mentioned paying particular attention to the orange and blue used in this book. Which colors did you finally settle on and why do you feel they are the perfect colors to tell the story of Testament?

>>Jonathan:

I said this before, but I like using a pretty simple approach to color. I like working with color but it just takes me so long and since I also like working with a more sparse palette it is just faster to go with the simpler one.

Since I was only going to use two colors I wanted to make sure those colors were perfect individually and balanced each other well. I needed a darker value and a medium value. I knew I needed the darker value to be a dark rich blue because I wanted it to function as a strong lineart color, but also as a deep dark night. Something close to black in some light and full of color in another. Likewise, I wanted the medium color to feel warm but not too saturated. Dusty. Although I had already been heading in that direction, that decision was validated after a trip to Badlands National Park which has a lot of rock formations with bands of earth in similar colors.

We ran into an issue with the first proof where the color that I wanted to be a dusty salmon, coral color just between pink and orange was BRIGHT orange. It hurt the eyes to look at it. Thankfully we were able to resolve it and get just the right color paper, and inks and I’m pleased with how it turned out in the end.

>>Mili:

What strengths of comics as a medium helped you tell this story?

>>Jonathan:

One huge strength of the comics medium is I can do it! That is kind of a joke, but I seriously think that a big strength of comics is simply that although they are labor intensive, one person can make them. And sometimes I’m lucky enough to be that person. If this were a movie we’d need way more people and way more money to do it, and I was already pretty surprised I could get a comic publisher who was down for a story like this. Can you imagine trying to get this made as a movie? I mean, who knows, if anyone reading this has millions of dollars and wants to let me make a movie let me know!

Besides all that, there is a lot to be said about closure and panel transitions helping create an easy but imaginatively active experience for readers. When a reader tells themself how one panel connects to another they are investing themselves in the story in a very small way. I try to think about storytelling as preparing a meal for someone but you don’t want to forcefeed them. I try to give people just enough that they can fill in the rest and I think comics are a great medium for that.

Also, I get to draw! And write! It’s magic!

On process ——————————————————————————————————->

>>Mili:

Many of these pages feel as if they are taken straight from your wonderfully rendered sketchbook. What was your process for drawing this book? To what degree are you a regimented step by step artist and to what degree do you change things on the fly?

>>Jonathan:

I wrote the whole book out as a script before I started drawing any pages. I did a little visual development at this stage but honestly not a lot until the second or third draft of the script. I don’t like rewriting after I’ve started drawing pages. This is actually the only project I’ve written that made me cry and it made me cry when I wrote the script, when I edited the script, when I was drawing it. Pretty much every stage, always at Judith’s death.

I do some extremely loose thumbnails as I write my scripts. Just empty panels with numbers in them to measure out the general flow on the page. After the script is figured out I sketch out the page pretty loosely. When you’re working with other people tighter pencils are important but when you are doing it all yourself you can leave a lot of the visual problem solving for the ink stage, and I like that. I would sketch out pages either on photoshop, which I don’t really like, and then use a lightbox when inking or just directly on the page with a pencil. I don’t like drawing digitally, but I like doing my colors that way.

I tend to be a pretty messy draftsman, I will build up the surface of a page with layers of ink and wite-out and paint, and patches of paper, etc. A lot of the textures I get are actually ink on top of white paint and scanned on a black and white threshold. I don’t think I could do them without those layers of mistakes and adaptation. People are like that too, I guess.

>>Mili:

How long did it take for you to draw all 118 pages Testament? Were there any moments during the book where you reached an artistic standstill and what helped you move through them?

>>Jonathan:

I always keep track of all the time I spend on projects but I’m not great at keeping track of how long individual steps take. All told the project took a little over 1000 hours, to write, edit, draw, and produce. I had help with the book design and publishing, of course, so some of those hours were spent in meetings or emailing back and forth.

It is a safe bet that it took at least 800 hours to do all the drawing.

>>Mili:

Your book is incredibly dialed both in story, pacing and artistic execution. Do you have any secrets that you want to share?

>>Jonathan:

Thank you! I touched on this already but I think, for me, giving the reader just enough and no more was the secret for this book. In another life, I have a whole TV series written in this world, with lots of different characters and subplots and stuff, but for this book it had to work with as minimal elements as possible while inviting the reader to put themselves in it.

When I had initially talked to my publisher, Zach, he wasn’t looking for longer stories and the first full version of this book was only 76 pages long. The story was complete in that shorter version, but he let me go back and redraw some scenes to have better pacing, introduce some moments of quietude and spaciousness, and extending the whole thing to 118 pages. That is still a short book, of course, but I think if I have a secret to share it is to make the story work in as short of a time span as possible and then add to it support those essential elements.

MISC ——————————————————————————————————->

>>Mili:

What didn’t I ask that you’d really love to talk about?

>>Jonathan:

That’s a fun question!

We didn’t talk about food. It was important for me to have a lot of scenes Testament growing and cooking food even though they cannot eat. I don’t think the Order of Benevolent Grace of the Cosmic Christ has a strict rule about eating meat, but I think they would have more vegetarians and vegans than other folks. This new planet is fairly edenic and I imagine there are no predatory animals. Maybe some scavengers. Humans are the most violent animal on the planet and I think out of respect for the lack of predation on this world, none of the humans in the expedition eat meat.

I’d love to talk about ecclesiastic fiction in general. It has become a pet genre of mine. Two of the novels that influenced Testament are Shusaku Endo’s Silence, and The Sparrow by Mary Doria Russel. There were a lot of other things, of course, but these are two novels about people in monastic groups facing doubt and despair in extreme situations. There may be others, I don’t actually read very much science fiction, but The Sparrow was the first scifi book I’d read that I felt intelligently approached religion in the future.

>>Mili:

What are some fantastic comics you’ve read this year that you’d like to recommend? Which comic artists are you watching?

>>Jonathan:

->Mili’s note 1, Betty’s Book’s has a fantastic podcast called Comics Closet, please listen and encourage them to make more

I really got into Taiyo Matsumoto recently, and I won’t shut up about him. I started with Tokyo These Days, which is one of my all time favorites, but I’ve also started on Sunny and I’ve got Cats of The Louvre, Tekkonkinkreet, and Ping Pong waiting on my To Read Shelf. I also recently finished reading Maison Ikkoku, an 80s romantic comedy manga series by Rumiko Takahashi before she did Ranma and Inuyasha. That was great. A quick shout out to Betty’s Books in St Louis! Betty and Alex introduced me to a lot of my favorite recent comics, a lot of which have been manga. I buy a lot of my comics from them, even though I don’t live there anymore.

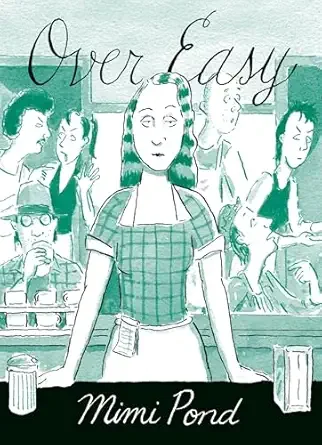

They aren’t really recent reads but some of my favorites I recommend to everyone are Ducks by Kate Beaton and The Hard Tomorrow by Eleanor Davis. Beaton and Davis are both big inspirations on me as an artist. My fiancee is reading Fun Home by Allison Bechdel right now and I’ve been doing that annoying thing where you watch someone read a book you like to see if they like it.

There are so many exciting things happening in indie comics these days. I feel lucky to have any readers at all when there are so many cool people making amazing things. One book I’m especially excited for is Someday Perfect by Kat Schneider. Kat and I have been internet friends for a while, and we actually got to meet in person when I asked her to come down from New Jersey and do a reading from Someday Perfect at my book launch party for Solace County 3. It is a YA comic about a girl at a religious camp, and it looks really interesting. Kat and I both grew up with pastors as fathers and we both have our debut graphic novels coming out at about the same time, and they both explore religion!

>>Mili:

What are you working on next?

>>Jonathan:

I’m currently working on the next volume of Solace County and trying to get working on the next graphic novel. I have a few ideas rattling around and I need to make myself do all the hard work of distilling some of those ideas into a cogent pitch and trying to find a publisher. It is hard to find the time or mental space.

I’m excited to say I am currently working on a collaborative story for the next Solace County with one of my favorite illustrators. Who knows if I will stick to it, but I’d like to have one story in each volume that I’ve worked with another person on.

>>Mili:

Where can people read Testament? And how can they support you and your work?

>>Jonathan:

You can order it from my publisher, Bulgilhan Press, directly from me, or ask your favorite local bookstore to get some copies. Never buy anything from Amazon.

You can support my work directly by checking out my online shop, hiring me for freelance illustration or teaching gigs, or signing up for my patreon so I can mail you drawings!